What will we do when the wells run dry? How about refilling the wells before that happens?

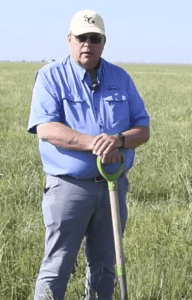

Chris Grotegut has gone crazy. There is no other explanation. In a world that has seen more and more grasslands being plowed up every year for row crop production, Chris has taken most of his irrigated cropland near Hereford, TX and planted it back to non-irrigated native grasses. This is in a region where corn is the king of the massive feedlot and dairy kingdoms that surround his 11,000 acres. He must be crazy, right? Why else would someone do the exact opposite of what everyone else in the area has done for over a century?

Chris Grotegut has gone crazy. There is no other explanation. In a world that has seen more and more grasslands being plowed up every year for row crop production, Chris has taken most of his irrigated cropland near Hereford, TX and planted it back to non-irrigated native grasses. This is in a region where corn is the king of the massive feedlot and dairy kingdoms that surround his 11,000 acres. He must be crazy, right? Why else would someone do the exact opposite of what everyone else in the area has done for over a century?

Maybe it is because Chris is crazy… like a fox. He saw how decades of excess tillage, bare soil and crop rotations based on shallow rooted corn turned his area soils to powder that blow in the wind, creating dust storms. He saw too much water being pumped out of the aquifer and was able to do the math and the numbers were ugly: he had only a few years left of irrigation before the wells would run dry. What happens to all those corn acres once the irrigation dries up, he asked himself. About a decade ago, Grotegut realized that he had to start pumping much less groundwater out of his wells. If he didn’t act soon, there may not be enough water to sustain his current operation, much less to support the next generation on his land.

So, Chris took the leap and did what he figured would need to be done at some point in time anyway. He began planting his cropland back to the native grasses that once covered his area before the plows and pivots and feedlots turned it all to corn and began grazing again. Then he discovered something rather amazing. The water level in his irrigation wells started rising.

The static level of water in all nine monitored wells on Grotegut’s land have been steadily rising. Between 2014 and 2019, on average, the wells rose by almost 7 feet, slightly over 1 foot per year, with one well seeing an increase of more than 12 feet. If you think these numbers are a mistake, you aren’t alone. The Texas Department of Agriculture thought it had to be a mistake too, so they replaced the well monitoring equipment, and it said the same thing. The water level is coming up. In the middle of a drought. In the arid Texas Panhandle. Despite the “experts” saying it could not happen. How can such a thing be possible? After all, haven’t we all been told that it is impossible to save the aquifer in our lifetime because it takes thousands of years for the aquifer to be replenished?

Chris believes the key factors to this rise are the reduction in water use and a reduced level of evaporation coupled with a vastly improved infiltration rate of rainfall. Better soil residue and soil aggregation and large macropores created by grass roots, earthworms, and dung beetles all contribute to water moving into the profile at levels simply not seen in the bare, tilled cropland that is common in the area. Given that the entire economy of the area is based on a level of irrigation that will likely deplete the water source upon which it relies within the next two decades, what happens when the wells run dry? Will everyone have to pack up and move? Will all the land simply be abandoned to blow away in dust storms like a repeat of the 1930’s? Chris is demonstrating that there is a viable alternative to this apocalyptic scenario, and the simplicity and practicality of his solution is amazing.

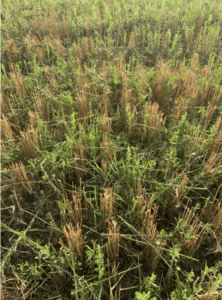

Spring remnants of winter crops planted over dominant grasses the previous winter.

So far, Chris has converted about 7,600 acres to perennial grassland with a diverse mix of warm-season grasses including blue grama, buffalograss, and sideoats grama (the state grass of Texas) waving in the summer breeze. During the fall and the winter when these warm season grasses go dormant, Grotegut takes a page out of the Colin Seis’s pasture cropping manual and seeds the fields with wheat, triticale, oats, barley, and canola along with winter legumes to grow until the warm season perennials begin their growth pattern again. (To learn more about pasture cropping, visit www.winona.net.au)

“We pasture crop right into the grass,” explained Grotegut, “as the key is leaving the soil and grassland undisturbed, so it’s as close to the native ecosystem as possible.”

One of the keys to success with this large scale conversion process has been the great biodiversity that Chris has allowed to occur through the natural process of plant succession. Starting with annual broadleaf weeds, the diversity of plant species has gradually shifted to a really nice mix of native species that are very well  adapted to west Texas conditions. The pasture cropping of annuals gives and additional biological boost when conditions allow it to happen. The biodiversity of plants above the ground, the biology below the ground and the animals on the ground is one of the main reasons that the water cycle is healing, the nutrients are now cycling, carbon is being restored to the soil where it belongs. When all of these ecocycles begin to heal, the land becomes much more resilient to all weather conditions, but especially drought.

adapted to west Texas conditions. The pasture cropping of annuals gives and additional biological boost when conditions allow it to happen. The biodiversity of plants above the ground, the biology below the ground and the animals on the ground is one of the main reasons that the water cycle is healing, the nutrients are now cycling, carbon is being restored to the soil where it belongs. When all of these ecocycles begin to heal, the land becomes much more resilient to all weather conditions, but especially drought.

Like most natural cycles, the methods in which water cycles through Grotegut’s land is complex. With his improved infiltration due to perennial grass plant roots, most of the water now stays in the field, but what is leftover filters into nearby shallow playa lakes scattered throughout the Great Plains. The playa lakes, which can dry up quickly from evaporation, go through cycles of wet and dry and are responsible for filtering and recharging an estimated 95 percent of the water to enter the southern portion of the Ogallala Aquifer. Grotegut has even been able to recharge the water in the part of the Ogallala Aquifer northwest of the playa lakes, located in the opposite direction that water flows. Between 2014 to 2019, the water levels in the northwest portion of his property went up by 2.22 feet. It saw the smallest increase out of all his wells, but still shows that recharge is possible.

Wet playas provide important habitat for migrating and breeding birds in the Central Flyway of North America.

After an initial loss of profitability while transitioning to perennials from conventional row crops, Grotegut has seen his profits rise. Huge reductions of expenses were realized from the cost savings of not pumping groundwater and greatly reduced input costs of a grazing operation versus cash cropping. Despite his success, he foresees that climate change will bring more challenges. During some periods of drought, he may decide to go without irrigation and, therefore, cash crops. But his cattle and sheep will bring in money for the farm, along with grains stored during the less dry years. “Failed crops are still grazeable, just like grass is,” he said.

All this means that Chris must plan carefully according to weather forecasts. If a wet year is predicted, the plan is to aggressively plant the winter crops so the roots soak up moisture. The following year, he’ll look for a deep-rooted plant to chase the remaining moisture, like sunflowers or cotton. Grotegut has also started rehabilitating some playa lakes on his property, which have been disturbed by earlier farming practices.

All this means that Chris must plan carefully according to weather forecasts. If a wet year is predicted, the plan is to aggressively plant the winter crops so the roots soak up moisture. The following year, he’ll look for a deep-rooted plant to chase the remaining moisture, like sunflowers or cotton. Grotegut has also started rehabilitating some playa lakes on his property, which have been disturbed by earlier farming practices.

“The ultimate solution is to reward farmers for encouraging water infiltration and conservation by allowing them to pump the amount of recharge their wells experience every year. That way, we can pump indefinitely, and those who conserve the most water also get to pump the most water. Now that we know it is possible to recharge the aquifer, we need policies that encourage it, rather than continuing down our current path that is guaranteed to leave us stranded in the middle of a desert within our lifetime.” Ultimately, Grotegut sees his transformation as being rooted in soil health, he said. “Our journey started off as a water table concern and ended up as a soil concern.”

This article first appeared in the 9th Edition of Green Cover's Soil Health Resource Guide.

Also check out the 11th edition, our latest Soil Health Resource Guide, over 90 pages packed with scientific articles and fascinating stories from soil health experts, researchers, farmers, innovators, and more! All as our complimentary gift to you, a fellow soil health enthusiast!