Everyone wants better food… but how can we easily tell when the food we are buying is just “OK” versus truly great? The Bionutrient Food Association has been focusing on Nutrient Density for over 10 years. We are an educational non-profit organization whose mission is to increase quality in the food supply. By quality, we mean flavor, aroma, nutritive value and health giving attributes. We understand that these aspects correlate to soil health, eco-system function, pest and disease resistance, and farm viability.

Our first five years were spent presenting workshops, 2-day courses called Principles of Biological Systems (available to watch on YouTube), running our annual Soil and Nutrition Conference (available to watch on YouTube) and establishing local chapters. As we worked with growers across the US and beyond it became more and more clear that working with life seems to be beneficial for soil, plant, animal, farm and human health. While this may be true, it seems like money is a driving force in today’s world and so we worked to figure out a strategy that could align these benefits with economic self interest. In other words, how could we help people make more money by doing the right thing? Quantifying nutrient density is critical because not all food is grown equally and looks can be deceiving. A visual inspection will not tell us which food is more nutritious than others. For example, is this cut of beef more nutritious than a similar one right next to it in the butcher case? Or is this bucket of wheat more nutritious than the next bucket?

Since it is consumers who buy food, and care about their health and the health of their families, then they should be the ones to choose and vote for the best with their food dollars. If we can give them the ability to discriminately purchase based on nutrient density, then higher quality food will be purchased first and the economic lever to encourage better food production will have been pulled. In a nutrient dense market model, the producers who are growing the best quality products would earn premiums for the crops they are producing and that would give a strong incentive to shift practices across agriculture.

We started working on the nutrient density project in 2016. We identified three steps that would need to be accomplished to be able to realize this vision.

- Confirm that nutrient variation in food is significant, and characterize that variation.

- Confirm that the nutrient variations in food correlate to management practices, fertility programs and soil health metrics.

- Build instruments that could be calibrated to those nutrient variations, and that could be used by consumers non-invasively at point of purchase, with a relatively simple hand-held device.

We started building the meter in 2017. By the end of the year the first version of the Bionutrient Meter was unveiled to our community at our annual conference. In 2018, we started our first lab, and assessed our first two crops, carrots and spinach. A variety of samples were sent in from stores, farmers markets and farms, both organic and non-organic. The samples were assessed for a suite of elements (Ca, Mg, Fe, Mn, K, Cu, P, S etc), as well as polyphenols and antioxidants. The nutrient levels in these crops had a huge variance, from 3:1 for calcium measurements in carrots to 15:1 for iron levels in spinach. That means that one leaf of the best spinach has 15 times the iron as one leaf of the worst spinach – even though they may not look that much different. When it came to testing the polyphenol and antioxidant levels, the variance was as much as 50:1 from best to worst!

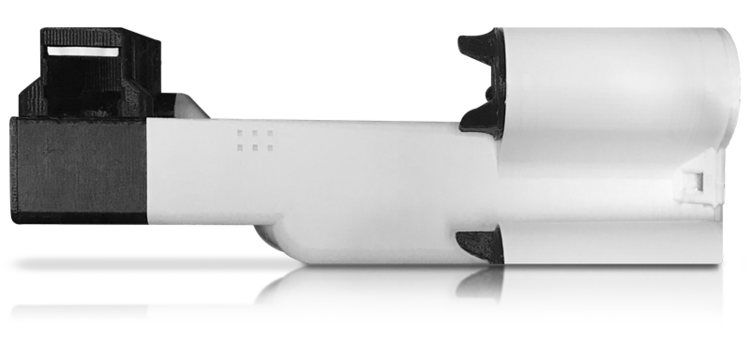

The Bionutrient Meter is a handheld spectrometer that works through the principle of spectroscopy to honestly assess food nutrient quality in real time. The Bionutrient Meter has lights (LEDs) that emit light at very specific wavelengths, which then bounce off objects like carrots, carrot pulp, spinach, or soil. Some of it is absorbed by the object and turned into other forms of energy, like heat. A light sensor in the device reads how much light bounces back for each wavelength very quickly and multiple times throughout a given measurement.

We believe that information about the nutritional value of food belongs in the commons, and so are committed to all of our work remaining an open source. That means that any and all research we do, any data we come up with, any engineering of instrumentation, and algorithms, apps, and code we develop will stay open so that everyone involved knows that they can trust the readings we develop.

In 2019 we set up our second lab in partnership with Chico State University and increased the number of crops sampled and tested to six. The team worked with the growers to document the management practices and fertility programs of the crops they submitted as well as assessing the soil the crops grew in so that we could overlay causal dynamics with soil metrics with nutrient variations. In 2020 we set up our third lab in France and increased the number of crops assessed to over 20 while working with over 200 farmers to submit samples of crop, soil and management data. Additionally, citizen scientists across the world have been sending in samples of crops from points of purchase for bionutrient testing, as our objective is to characterize the variation in the retail supply chain.

By the end of 2020 we had enough data to confirm that across almost 2 dozen different crops, from roots to leaves to fruits to grains, nutrient variations are quite significant, with orders of magnitude similar to the first data collected in 2018. We were also able to show with confidence that management practices that increased soil health had a direct and strong correlation to increased nutrient levels in crops and produce. At this point we also had enough data to build calibrations for our basic handheld spectrometer so that anyone could use it at the point of purchase. The meter gives the user meaningful results for nutrient levels, whether antioxidants, polyphenols or BQI, our stand in for nutrient density which includes six elements and two compounds. In 2021, we released a second generation of that spectrometer, calibrated to 10 different crops.

By the end of 2020 we had enough data to confirm that across almost 2 dozen different crops, from roots to leaves to fruits to grains, nutrient variations are quite significant, with orders of magnitude similar to the first data collected in 2018. We were also able to show with confidence that management practices that increased soil health had a direct and strong correlation to increased nutrient levels in crops and produce. At this point we also had enough data to build calibrations for our basic handheld spectrometer so that anyone could use it at the point of purchase. The meter gives the user meaningful results for nutrient levels, whether antioxidants, polyphenols or BQI, our stand in for nutrient density which includes six elements and two compounds. In 2021, we released a second generation of that spectrometer, calibrated to 10 different crops.

At this point of the project, we feel that we have completed the proof of concept and now we need to go to the next steps of the project. We need to define nutrient density, and build the instrumentation necessary for the supply chain to begin to be able to make management and production decisions based upon the definition. In the next 5 years, we intend to define standards for nutrient density for the top 20 globally produced crops. We will support the establishment of instruments and will work hard to develop a market that based on nutrient-dense economic transactions that will encourage and reward growers for their improvements to the soil health of their fields.

Our first “crop” for this next stage is beef. We are working with leading researchers to identify the range of nutrients and compounds that vary in beef products based upon how it is produced. To accomplish this goal, we have established a data collection framework that will not only assess the meat for almost 800 elements and compounds, but will also asses the micro-biome of the cows that produced it, as well as the forage or fodder they consumed, the soil it was grown in, and management practices that were applied. This project will collect three beef samples from 200 global growers across the management spectrum, as well as 150 supermarket samples to establish sufficient data to build a first definition of Nutrient Density in beef.

As a part of this project, we will also be able to provide every participating producer with their herd data that can be shared publicly. This allows the best producers to make and support favorable nutritional claims to their customers. The cattlemen will also have access to the testing results of their micro-biome, soil, forage, and management data in comparative context to all other growers in the project so that they may be able to discern ways in which to improve. This data framework promises complete anonymity to participants and can be used by other growers to assess their own management practices and work to improve them based upon the guidance arising from the collective.

Our partners have also initiated human trials with beef from the both the high end and the low end of our Nutrient Density spectrum to bring the final piece to bear: the connection to human health. When completed, this data will be published in peer-reviewed journals. We have chosen beef first because it is the crop with the largest global market, largest global land footprint, and therefore the crop with the ability to affect the largest global shift towards climate health. Also, there are a number of producers already providing high quality beef actively interested in being able to differentiate themselves in the market based upon nutritional claims.

As we enter 2023, we are beginning to branch out beyond beef in this nutrient density program. Those who are interested in engaging in the project should feel to email us at partners@bionutrient.org, or to review the work of the BFA and BI at www.bionutrient.org and www.bionutrientinstitute.org.

This article first appeared in the 9th Edition of Green Cover's Soil Health Resource Guide.

Also check out the 11th edition, our latest Soil Health Resource Guide, over 90 pages packed with scientific articles and fascinating stories from soil health experts, researchers, farmers, innovators, and more! All as our complimentary gift to you, a fellow soil health enthusiast!