Pasture management for horses

By Dale Strickler

It is important to have realistic expectations of yield per acre and an accurate estimate of acreage to determine carrying capacity. There are biological limitations to how much vegetation can be produced on an acre. Typically in Kansas and Nebraska, moisture is the most often limiting factor to pasture growth. At the eastern edge of these states, there is usually over 30 inches of annual rainfall, while at the western edge there may be less than 15. The stocking rates below give a rough guideline for reasonable stocking rates for the usual 5 month pasture season, adjusted for rainfall. Note that these recommendations are likely for much larger acreages per horse than is often recommended for horse pasture in the more humid rainfed areas in the eastern US. The “1 acre per horse” guideline that is often cited may be valid in Iowa or Kentucky, but not Kansas or Nebraska. If the acreage is uncertain, an acre is 43,560 square feet, or approximately the size of a football field. Measure the length and width in feet, multiply and divide the result by 43560 to get the acreage.

Acres required per mature horse with appropriate management |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

Annual Rainfall (inches) |

15 |

25 |

35 |

| Fertilized cool season grass, or grass-legume mixture |

8* | 4 | 3 |

| Warm-season native grasses | 12 | 8 | 5 |

| Fertilized Bermudagrass (Kansas and the South only) |

4* | 2 | 1 |

| *may require some supplemental irrigation to establish and/or thrive | |||

These acreages may be reduced if irrigation is used. Irrigated pasture requires 1 inch per week during the growing season less any rainfall received, with up to 2 inches per week during particularly hot weather.

Grazing Management for Horses

Probably no other domestic animal has more potential to destroy a pasture than horses. Because of their tooth structure, horses are capable of biting grass almost to ground level, and will do so if allowed. There is no grass that will thrive under this form of grazing, and most will not even survive. It does absolutely no good to plant the absolute finest pasture species and then fail to control the grazing pressure and kill the pasture. It is your job as a pasture manager to prevent this form of grazing. Plants grow through photosynthesis, and it takes leaf area to perform this task. Anytime sunlight strikes bare soil, that sunlight is NOT being used to grow feed and is wasted potential feed. It should be a primary goal during the growing season to never have bare soil. In fact, most pasture grasses should be maintained with a minimum stubble height of 4 inches throughout the entire season. If horses have continuous uncontrolled access to a pasture, this can never be achieved. Even with plenty of acreage allowed, horses will return to eat the tender regrowth of plants they have previously grazed, and ignore the tall, rank growth of adjacent ungrazed plants inches away. Rotational grazing is a powerful tool to maintain healthy pastures with horses. Pastures should be subdivided into at least 4 paddocks, with more being advantageous. The easiest way to do this is to have electric fences radiating out from a water source into the pasture. Paddocks do not need to be the same size to be effective. These paddocks can be further subdivided with polybraid wires on reels and step-in fence posts to allow moves as frequently as daily. Moving daily is far more efficient than less frequent moves. There should be at least 8 inches of growth in a paddock upon initial entry. When the grass is grazed down to 4 inches, move to the next paddock and repeat the process. Return back to a paddock once regrowth reaches 8 inches or more. Now here is the important part: if regrowth has not reached a minimum of 8 inches, lock animals into a pen and feed hay rather than pasture. You can and probably should supplement pasture with hay, but NEVER use hay as a means to allow animals to stay on a pasture after the stubble height drops below 4 inches. Hay fed as a supplement during the growing season should be in an adjacent pen, rather than in the pasture itself. The two most common mistakes made by those beginning rotational grazing are 1) rotational overgrazing, that is trying to eat every last bit of the grass before leaving a paddock, and 2) trying to base movement dates on a calendar basis rather than on grass growth. It is very common among beginning rotational graziers, many of whom have a Monday through Friday full-time job, to tell themselves that they will have four paddocks and they will simply move every Saturday when they have time, and each paddock will get grazed once a month. This only works when each paddock grows exactly a week’s worth of feed at a time, which seldom if ever occurs. It is common for people on the “weekly move” plan to visit their pasture on Saturday only to find that during this time the grass has been grazed to bare dirt. In one study conducted in Missouri, grass grazed to 4 inch stubble height took 30 days to regrow to a 12 inch height, while grass grazed to a 2 inch stubble height took 45 days to regrow to a 12 inch height. The difference in a 4 inch stubble height and a 2 inch stubble height is often just one additional day too long in a paddock. Moving on Saturday when the move should have been done on Friday may have gained one days grazing on this rotation, but lost two full weeks of regrowth that will need made up at some point in time.

What if I have too many horses for the pasture I can produce?

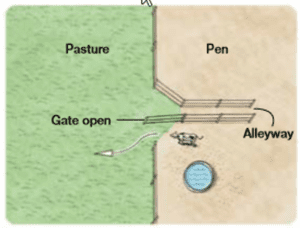

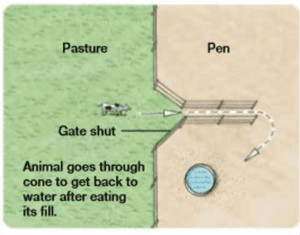

The obvious answer here is to either expand acreage or reduce numbers, but sometimes there is insufficient area to grow enough feed for even one horse, and it is hard to create a fraction of a horse. All too often the horse is fed hay as a supplement to a pasture that is of insufficient area, but the horse is given unrestricted access to the pasture and the horses eat every blade of grass in preference to the hay and eventually destroy the pasture. It is possible with creativity and planning to have a horse on an acreage of smaller size and still gain value from pasture. This can be accomplished through a concept called time limit grazing. The basic concept is to keep the horses locked in a pen adjacent to the pasture and allowed free choice hay, and let them out to graze for roughly an hour a day. This can also be done (and preferably so) in combination with a rotational grazing scheme. This creates a twice daily time commitment (once to open the gate, and then to chase them in and close the gate), but even this can be managed with creativity. There is a device called a Batt latch that opens a gate based on a timer, and allows an owner to be absent when the gate needs to be opened. Another innovation is called a fish trap gate. It uses the inverted cone principle to allow animals into the pen to get water after grazing, but they can’t get back into the pasture.

The obvious answer here is to either expand acreage or reduce numbers, but sometimes there is insufficient area to grow enough feed for even one horse, and it is hard to create a fraction of a horse. All too often the horse is fed hay as a supplement to a pasture that is of insufficient area, but the horse is given unrestricted access to the pasture and the horses eat every blade of grass in preference to the hay and eventually destroy the pasture. It is possible with creativity and planning to have a horse on an acreage of smaller size and still gain value from pasture. This can be accomplished through a concept called time limit grazing. The basic concept is to keep the horses locked in a pen adjacent to the pasture and allowed free choice hay, and let them out to graze for roughly an hour a day. This can also be done (and preferably so) in combination with a rotational grazing scheme. This creates a twice daily time commitment (once to open the gate, and then to chase them in and close the gate), but even this can be managed with creativity. There is a device called a Batt latch that opens a gate based on a timer, and allows an owner to be absent when the gate needs to be opened. Another innovation is called a fish trap gate. It uses the inverted cone principle to allow animals into the pen to get water after grazing, but they can’t get back into the pasture.

Pasture Plants For Horses

Since horses can graze so close to the ground, plants suited for horse pasture should be tolerant of severe grazing. This usually requires growing points and leaf placement close to the soil surface. With good grazing management (rotational grazing with adequate residual left after each grazing) the list of suitable plants for horse pasture expands greatly. More than any other domestic animal, horses prefer grasses over other plants. While grasses form the basis of a good pasture, legumes can be a valuable addition because of their ability to fix nitrogen and their higher protein content. Not all grasses are created equal. Warm-season grasses have a completely different physiology than cool-season grasses. Cool-season grasses begin growth in early April, form seedheads by late May, grow very little in the heat of summer, and then have a growth period in the fall with sufficient moisture. This is a much longer growing season than warm-season grasses. Cool-season grasses require more moisture and more nitrogen to produce a pound of forage than warm-season grasses. Despite their poorer water use efficiency, some cool-season grasses can be drought tolerant simply by going dormant during the summer. This aids survivability but obviously reduces forage availability in the summer. Cool-season grasses require a source of nitrogen in order to produce well, either fertilizer or an associated legume. At similar stages of growth, cool-season grasses are higher in protein and more digestible than warm-season grasses. Warm-season grasses begin growth in early May, begin to form seedheads in August, and go dormant around first frost in the fall. Despite their lower quality at similar growth stages compared to cool-season grasses, they usually have higher animal performance in the summer than cool-season grasses because they are at an earlier stage of maturity than cool-season grasses. All grasses decline in quality with advancing maturity. A pasture plan utilizing both warm and cool-season grasses allows for a better seasonal distribution of quality and a much longer grazing season than either one alone. Since the management of each is different, these should be in different pastures, rather than combined into one. Warm-season grasses should be pastured from May through August, and rested from September 1st through first frost. Cool-season grasses can be pastured in April after 8 inches of growth appears, and continuing until warm-season grasses are ready. They can be rested during the summer, and any accumulated growth pastured off beginning in September when warm-season grasses are being rested. Both can be grazed off completely in the wintertime without harm to the plants, although adequate soil coverage should be maintained to protect against soil erosion and evaporation

Warm-Season Perennial Grasses

Native prairie in the eastern part of Kansas and Nebraska typically consists of big bluestem, Indiangrass, little bluestem, switchgrass, and sideoats grama. In the western part of these states, it is primarily buffalograss and blue grama, with the central part being a mosaic of the two ecotypes. The bluestem prairie is more productive but less tolerant of overgrazing than the buffalograss plains. Buffalograss is tolerant of grazing to two inch stubbles, while the bluestem requires 4 inch stubbles. Usually these grasses are in preexisting stands, but it may be desired to plant new stands of restored prairie. This is not usually done because of the usual two full year establishment period of these grasses prior to first grazing season. This establishment period can be drastically shortened by inoculating seed with mycorrhizal fungi prior to planting. In a new seeding switchgrass should be omitted as it is very unpalatable to horses.

Suggested tallgrass mixture per acre: 4 lbs big bluestem, 2 lbs each Indiangrass, little bluestem, sideoats grama planted from January through May

Suggested shortgrass mixture: blue grama (1 lb) buffalograss (2 lb), sideoats grama (3 lb), planted January thru May

Bermudagrass is an introduced warm-season grass of lower quality than native grasses but with more yield potential and very good tolerance of hard grazing. It also establishes quicker than native grasses. In order for the higher yield potential to be realized, though, it requires nitrogen fertilization, to which it is quite responsive.

Suggested seeding rate 10 lbs per acre planted in May

Eastern gamagrass is a native grass with exceptional yield potential and good quality. However, the seed is quite expensive, it is slow to establish and requires very careful grazing management (12 inch stubble heights remaining after each grazing). It responds well to irrigation and fertility.

Suggested seeding rate 10 pounds of pure live seed per acre planted in January or February. After the first growing season, legumes may be interseeded.

Cool-season perennial grasses

Tall fescue is probably the most suited cool-season grass for horses, but only if endophyte free or better yet “friendly endophyte “ varieties are used. The predominant fescue variety Kentucky 31 (or K31 for short) is infected with a seed borne endophyte (means it lives inside the plant) fungus that causes the plant to produce toxins to which horses are particularly sensitive. Horses on K31 fescue seldom perform satisfactorily, and pregnant mares often abort and fail to milk if they do produce a foal. Most “turf type” fescues also contain this fungus. Endophyte free varieties will produce far superior animal performance to K31. The fungus is not all bad, however, as it somehow causes the plant to be more heat and drought tolerant. This is why the friendly endophyte fescues (or novel endophyte, or nontoxic endophyte as they are sometimes called) were developed. They combine the heat and drought tolerance of K31 with the superior animal performance of the endophyte-free varieties. Tall fescue is very tolerant of hard grazing (though it also responds well to the recommended 4 inch stubble minimum) and has the unique ability to retain good grazing quality well into the winter if left ungrazed in the fall. In a pure stand, plant 20 lbs per acre either from March 15-April 15, or Aug 15-Sept 15. It is a bunchgrass, but does form solid turf.

Timothy is a grass which is often associated with horses but has little value as pasture in Kansas. While it makes good quality hay, it is very intolerant of close grazing, and does not tolerate heat or drought well.

Kentucky bluegrass is another grass often associated with horses, because it is very tolerant of close grazing. Despite its tolerance of close grazing, it is low yielding and has very poor heat and drought tolerance and thus should not comprise a high percentage of a pasture mixture. It often largely dies out in the summer and recovers with fall rains. Because it does have such good tolerance of horse grazing, it is a valuable addition to a mixture at 1-2 lbs per acre. It is a sod former and thickens over time.

Smooth bromegrass is one of the more drought tolerant cool-season grasses and is very palatable to horses. Despite its ability to survive on lower rainfall than other cool-season grasses, it achieves this feat with a high level of summer dormancy and furnishes very little summer forage. It is also very unproductive when grazed closely, but does recover well when properly grazed. It is a sodformer and stands thicken over time. In a pure stand, it should be seeded at 20 lbs per acre from March 15 thru April 15, or Aug 15 thru Sept 15.

Western wheatgrass is a native cool-season grass that is one of the most drought tolerant cool-season grasses, but is low yielding and of relatively poor quality. It has the most utility in the western part of the state where other cool-season grasses do not thrive. Even so, it is best used in a mixture where it has the primary value of often being the sole cool-season grass to survive when other grasses of better yield and quality are killed during prolonged drought. It forms a loose sod and spreads well. A pure stand is 10 lbs per acre.

Orchardgrass is a bunch grass that is productive and palatable to horses. It is usually short-lived in Kansas and Nebraska, and is not as tolerant of heat and drought as brome or fescue. It is of most value in combination with longer lived grasses. Pure stand is 12 pounds an acre.

Meadow brome is a bunch grass that has far better regrowth and fall production than smooth brome, which it resembles. It is probably underutilized in pasture plantings, but is best used in combination with sodformers. Pure stand is 20 lbs per acre.

Mixtures of cool-season grasses can combine positive traits of several grasses into one pasture. Mixtures are usually higher yielding and more resilient than a monoculture. They also allow for a “survival of the fittest” in which species sort out by suitability to soil type and grazing management. To create a mix, just take the pure stand seeding rate and use the same percentage of that rate as you desire in the pasture composition.

Legumes

Alfalfa is by far the most productive legume, and since horses do not bloat like cattle it has more utility in horse pastures than in cattle pastures. However, it is must be rotational grazed with rest periods long enough to allow blooming to occur before each grazing period. It will rapidly disappear under continuous grazing. It is very high in nutritional value and its ability to fix large amounts of nitrogen is a great boost to pasture productivity. In a blend with grasses, it can be planted at up to 6 pounds per acre at the same time as the grasses. It is compatible with cool-season grasses and eastern gamagrass.

Red clover ranks second to alfalfa in both productivity and nitrogen fixation. It combines well with cool-season grasses but is too competitive to warm-season grasses. In a blend with grasses, it can be planted at 5-10 pounds per acre. It is one of the easiest legumes to establish in an existing grass stand, and can be established by broadcasting seed in January or February into existing grass, or drilled at the time of seeding the grasses. It also requires rotational grazing in order to thrive. Plants usually only live three years, so it should be allowed to occasionally reseed, requiring at least a 60 day rest period. Occasionally red clover plants get infected with a black mold that is mildly toxic to horses (the toxic agent is called slaframine) and causes slobbering and an unthrifty appearance but this is usually found in the more humid eastern US and is seldom seen in Kansas or Nebraska.

White (dutch) clover is a legume that is of low yield but exceptional quality. It is unique among legumes in that it is very tolerant of hard grazing. It also spreads by stolons (runners) and thus thickens over time, even under hard grazing. It is the only common legume tolerant of hard, continuous grazing. It has poor tolerance of heat and drought, and often dies out during summer but recovers with rain. It is compatible with both cool and warm-season grasses. In a mixture, plant at 1-2 lbs per acre. It can be broadcast into existing stands in January or February or planted at the same time as cool-season grasses.

Ladino clover is a giant strain of white clover, and is roughly three times as productive, but shares the poor tolerance of heat and drought of white clover. While higher yielding, but does not recover as well after drought as dutch white.

Summer annuals

Pearl millet is a highly productive summer annual grass that can furnish abundant grazing in July and August. It should be planted in late May to early July at a rate of 15 pounds per acre, and can furnish grazing within 45 days after planting.

Crabgrass is a surprisingly good horse pasture in late summer, both in terms of productivity and nutrition. It can be broadcast seeded into existing cool-season pastures to improve summer productivity, or seeded into bare ground by itself or in mixture with other summer annuals as a dedicated summer pasture. In a pure stand, it should be seeded at 6 pounds per acre in May.

Teff is another summer annual grass that is most often used as a rapid drying, high quality hay, but can also be utilized as late summer pasture. It should be planted at 6 pounds per acre in late May to early July. It is important to place teff seed no more than ¼ inch deep, preferably at 1/16 inch deep.

Winter annuals

Wheat, rye, triticale, winter barley are all productive winter annuals for horses and can provide late fall and early spring pasture. They should be seeded at 60-120 lbs per acre in late August to September. Wheat is the least productive of these, and is susceptible to diseases when planted this early. However, wheat grown as a grain crop can often furnish incidental grazing without harm to grain yield if animals are removed prior to jointing stage of the wheat.

Plants that should NOT be grazed by horses

Sorghums, sudangrass, and sorghum-sudangrass hybrids can contain prussic acid to which horses are very sensitive and should not be pastured during the growing season. Sorghum hay, however, is free of prussic acid and is safe to use for horses.

Foxtail (or german) millet contains a compound that causes joint pain in horses. It should not be used for either hay or pasture.

Hairy vetch, crimson clover, and arrowleaf clover are all unpalatable to horses. Hairy vetch contains toxins to horses, while crimson clover can cause hairballs in the stomach and colic.

Illinois bundleflower is a native legume often planted in native grass blends. While not toxic to horses, it is very unpalatable to them.

Ryegrass (either perennial or annual) is of exceptional quality, but is actually TOO HIGH in sugar content for horses and can cause founder issues. Perennial ryegrass also lacks the heat and drought tolerance for use in any but irrigated pastures in most of Kansas and Nebraska. Ryegrass hay has usually lost enough of its sugar content during curing to be safe for horses however.