Improving profitability of brome and fescue pastures through interseeding.

Nitrogen fertilizer makes grass grow. No one questions that. Nitrogen fertilization is a proven way to increase grass yield. But the recent and dramatic rise in the cost of nitrogen fertilizer has many people questioning whether or not they want to spend that kind of money to fertilize their pastures and hay meadows consisting of smooth brome, tall fescue or other cool-season grasses. Many people have realized it is just hard to pencil a profit on an acre of monoculture cool-season grass once you factor in the additional nitrogen cost.

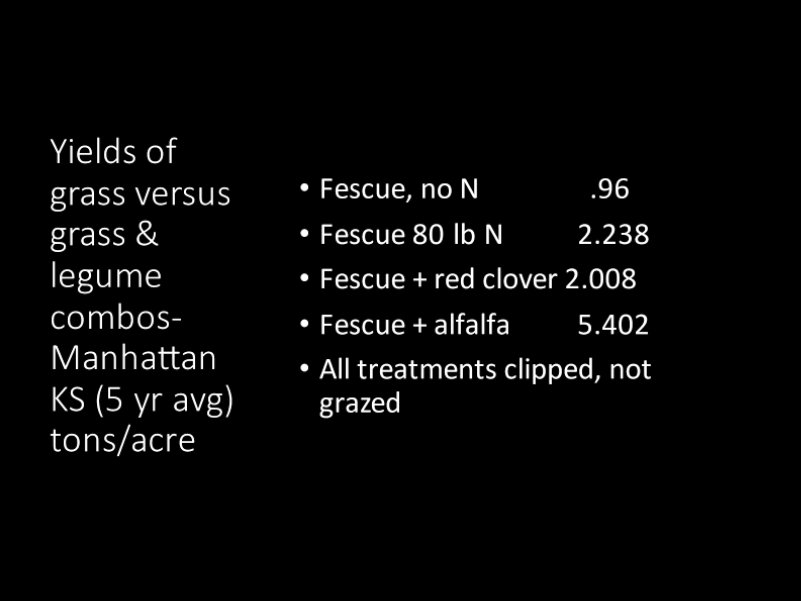

This realization has led many to explore interseeding legumes into otherwise monoculture grass stands to eliminate nitrogen fertilizer costs. Legumes are not the only option, however, and many other species also deserve consideration. Including a complex blend of legumes and forbs into a grass stand can greatly increase production, as shown by the table below:

Photo above: Note the much higher production from the plot on the left which includes alfalfa, clovers, chicory, and plantain than the monoculture fescue to the right of the orange line. A more diverse pasture will be much more productive and support much better animal performance than a monoculture, especially if that monoculture is K31 endophyte infected fescue.

There are many species that can be interseeded into brome or fescue, and below we have described several. All of the species listed below have situations in which they can increase productivity or decrease input costs in some manner. Note the seeding rates given below are for a full rate of a single species. If planting in a blend, these rates would be reduced accordingly to the percent of the final mixture desired of that species. Here are some potential species of consideration:

Perennials and/or reseeding annuals (these could be seeded once, and can increase production for several years)

Red clover is the most popular interseeding option in brome. Part of its popularity is due to how easily it can be established, as it has good seedling vigor and can be established easily by broadcasting. Red clover is a moderate nitrogen fixer, and is fairly productive. Plants typically only live two or three years, so they either need to be allowed to reseed (which takes a 60 day rest period to allow seed formation) or should be reseeded every second or third year. Recommended seeding rate is 10 pounds per acre, broadcast in mid-winter or drilled either fall or spring. Red clover rarely causes bloat.

Ladino clover is also a popular option. It is not as productive as red clover, but it spreads by stolons (runners) so it will thicken over time. The forage quality is excellent. Although ladino clover can cause bloat, it is very infrequent because it is hard for animals to get a bite of the low growing ladino without taking in a greater amount of associated grass. It can be established also by broadcasting in midwinter, or drilled in spring and fall. Five pounds an acre is recommended.

Alfalfa is far and away the most productive legume, but it is quite bloat conducive and does not tolerate continuous grazing. If alfalfa is used, it should either be hayed, or rotationally grazed, with a minimum of four paddocks, and grazing periods beginning at bloom and lasting no longer than a week on each paddock. Alfalfa is best established by drilling 2 pounds an acre in a mixture in either fall or spring. In a pasture seeding, a full rate of alfalfa such as the 12-20 pounds per acre recommended on cropland, is not desirable.

Korean lespedeza is a summer annual legume that is low-growing and not very productive, but the production comes at a time when brome is not very productive, in July and August. Do not confuse Korean lespedeza which is highly palatable, with the noxious unpalatable weed Sericea lespedeza. They are only distantly related. Lespedeza has a couple of other advantages as well. It is tolerant of 2,4-D so it can allow for the control of broadleaf weeds if desired. It also contains condensed tannins, compounds that can complex with the bloat-causing protein in alfalfa and clover and thus help aid in bloat control. It can be established by broadcasting 10 pounds of seed an acre in midwinter, similar to the clovers. It reseeds itself very well once a stand is established.

Chicory is a forb, not a legume, so it does not fix nitrogen. It has other attributes that make it very desirable, however. Like lespedeza, it contains tannins that help prevent bloat. It also contains compounds that reduce parasitic worms. It has exceptionally deep roots and seems to thrive even in very compacted soils. It is very digestible and has an unusually high mineral content, and studies indicate that its inclusion in pasture mixes increase animal performance. It can be established by drilling 5 pounds of seed an acre in early spring. It does not cure well in hay, so it is best used for grazing.

Plantain is another forb, and has similar nutritive characteristics as chicory. It is somewhat less productive than chicory, but does exceptionally well in heavily compacted soils compared to other species. It is a primary choice in high traffic areas with compaction. It also has been demonstrated to boost the immune system of animals, preventing illness. A pure stand rate is 5 pounds an acre, in a mixture ½ to 1 pound per acre is recommended.

Crabgrass is a very productive and palatable summer annual grass that grows primarily in the heat of summer, when brome is unproductive. As any lawn owner can attest, it reseeds itself very well. Like other warm-season grasses, its productivity per day in high temperatures is much greater than cool-season grasses or legumes so it can add greatly to summer productivity. It can be established by either drilling shallow or broadcasting 3 pounds an acre in late spring.

Summer annuals (need planted annually)

Summer annuals can be seeded into an existing stand of brome or fescue that has been hayed or grazed down to reduce the competition from the perennial grass to the new seedlings. Timing should be after the peak growth of the grass has passed, just as the grass is about to enter its period of summer dormancy. For most of our customers, this will be in late June. Some species to consider for planting at this time include:

Teff is another warm-season annual grass like crabgrass. It is similar in productivity and palatability but does not reseed as readily while being hayed or grazed and thus has less weedy potential. This is the product of choice if it is desired to convert the land back to a grain crop. Like crabgrass, it can establish easily by broadcasting.

BMR grazing corn is an extremely productive and palatable species that has been used to great effect by some innovative farmers. As an open pollinated variety, it is very cheap to plant. It should be drilled in late spring after soil warms above 55 F, at up to 20 pounds per acre at an inch or more depth. It does not regrow after grazing, so it is best used to accumulate growth during the summer that can be grazed off in early fall. It does not reseed itself.

Popcorn is another possibility, it is not as palatable as BMR corn but the seed flows much better through a drill and there are more seeds in a pound, so it is easier to get a good stand.

Cowpeas are a summer annual legume that fix a great deal of nitrogen. They are similar to soybeans in growth habit and nutritional value but are more tolerant of heat and drought. They regrow well after grazing, as long as the stems themselves are not grazed off. Cowpeas do not reseed themselves very well. They should be drilled in late spring after soil warms up to 60 degrees F, at a rate of up to 40 pounds per acre, at an inch or more depth.

Sunnhemp is probably the most productive annual legume known, and produces the most nitrogen as well. It has hard woody stems, but the leaves are very high in protein. Most varieties contain alkaloids that make the plants rather unpalatable to cattle, although sheep and goats seem to find it palatable. The variety Tropic Sun is highly palatable to cattle, however, and animals grazing it perform exceptionally well. It should be drilled at a rate of up to 20 pounds per acre (pure stand rate) at a depth of an inch or more.

Forage soybeans are the same species as the soybeans used for grain, but tend to be later maturing and have a vinier nature than grain soybeans. Seeds of Laredo, a popular forage variety, are also much smaller and therefore fewer pounds are needed for a good stand. Soybeans can fix considerable nitrogen and are palatable and nutritious.

Mung beans are a small-seeded bean related to cowpeas. Compared to cowpeas, they grow just as rapidly but are shorter in maturity and therefore hit peak biomass early while cowpeas are still adding yield, so the yield potential of mung beans is lower. The small seed size makes them quite economical to plant, however. They are very palatable to livestock.

Spring peas are a cool-season annual legume that can produce a respectable amount of nitrogen in a short time in the fall or early spring. They should be drilled in either March or August, at rates up to 60 pounds an acre, at an inch or more of depth.

Okra is a broadleaf plant related to cotton and is often used as a garden vegetable. It is extremely tolerant of heat and drought and is very palatable to grazing animals. If combined with cowpeas, the cowpeas will use the okra as a living trellis to climb upon, which greatly increases the cowpea production.

Sorghums and Sorghum-sudangrass hybrids are probably the most productive summer annual species that can be interseeded into cool-season pastures. One sorghum variety in particular, the mis-aptly named Egyptian wheat, has been particularly productive when sod-seeded. It is not particularly of high forage quality, but yields exceptionally well. Brown midrib hybrids are more digestible than conventional hybrids. Sorghum-sudans, especially Dwarf hybrids are leafier and feature faster regrowth during grazing

than taller hybrids or forage sorghums. Sorghums of all sorts, but especially forage sorghums, can produce toxic prussic acid at the initial frost in the fall, so it is important that animals not be on a pasture containing sorghums during risk of first frost in the fall. Once frozen and dried, sorghum forage becomes safe again.

Sunflower produces a seedhead that is relished by grazing animals and is very high in energy density due to the oil content. It also is highly attractive to seed eating birds.

Gourds, pumpkins, and melons have vines which are not eaten by livestock, but the ripe fruit is very palatable and nutritious once animals learn to eat them. The fruit is high in protein and energy, and the seeds of cucurbits have deworming properties. The fruit typically becomes available in fall.

These options can be lumped into two broad categories: long-term option (perennials and reseeders) or temporary options (annuals that do not reseed). As might be expected, the temporary options are more productive in the short term, but do require annual reseeding.

Bromegrass regrowth 90 days after haying in a year with abundant moisture. Three months of summer sun and this is all the growth a brome monoculture could muster.

This is the same field as the photo above, but this is looking at the half of the field that was drilled to a mixture of summer annuals after hay harvest. How many more tons of grazeable forage per acre can this produce than the other half of the field? Clippings indicated this half of the field produced 1.5 tons more biomass per acre than the other half, and as a bonus, the following year this half outyielded the other half by an extra .35 ton of hay per acre.

Here is a suggested temporary summer grazing mixture for drilling into brome in late spring or summer.

- Egyptian wheat 5 pounds

- Sunn hemp 3 pounds

- Cowpeas 3 pounds

- Okra 1 pounds

- Oilseed sunflower 1 pound

Best results with the above blend is to allow the mix to grow for at least four weeks after seeding to allow sufficient growth.

Here is a suggested blend of long-term species to drill in early spring or August:

- Spring peas 20 pounds

- Red clover 5 pounds

- Ladino clover 1 pound

- Chicory 2 pounds

- Crabgrass or teff 1 pound (omit in August seeding)

- Korean lespedeza 1 pound (omit in August seeding)

- Plantain 1 pound

(if willing to rotationally graze and control bloat, these amounts can be cut in half and blended with 5 pounds per acre alfalfa)

Obstacles in establishing long-term options in brome and fescue:

Not everyone who tries to establish other forages in cool-season grasses succeeds. There are a number of potential problems that may occur that can prevent the establishment of a good stand. And no, “it just doesn’t work around here” is not one of the problems; if it doesn’t work there is a reason other than you happen to live in an area where the laws of physics, chemistry and biology are completely different than everywhere else in the world. Anticipating these problems can allow us to manage to prevent these problems and obtain a satisfactory stand. Here are several potential obstacles.

Surface soil acidity: Each pound of nitrogen fertilizer creates enough acidity to require 2 pounds of lime to neutralize it. Since most brome acres have a history of nitrogen fertilization over many years, there is a great deal of acidity, and it is all concentrated in the surface inch of soil. It is recommended to take a soil sample of an inch or less sample depth to determine if lime is needed. Many old brome fields have surface pH of 4.0 or even less. Few small-seeded legumes can survive pH levels this low. Remember, soil test lime recommendations are assuming you are trying to neutralize six inches in depth. If your sample depth was only an inch, divide the recommended lime rate by six. Freezing and thawing is usually sufficient to incorporate any lime needed to correct soil acidity less than two inches deep.

Insufficient phosphorus, potassium, and sulfur. Although most people are very diligent about applying nitrogen to brome, few are good at insuring an adequate supply of other nutrients. Soil test (this time with the standard 6 inch sample) and apply the recommended amounts called for.

The need to withhold nitrogen fertilization during the establishment year.

If stands are fertilized when trying to establish a legume, the legume will fail to nodulate and do poorly, and the brome becomes too competitive. Many hesitate to reduce nitrogen fertility, because they know doing so will greatly reduce yield. That is the logic behind including spring peas in long-term plantings, even though they are a short lived annual and disappear after the first year. The peas grow rapidly, and replace the yield lost by omitting nitrogen fertilizer in the short term. Once established, alfalfa and/or clovers will usually eliminate the need for nitrogen fertilizer.

Grasshoppers and crickets can often decimate seedling alfalfas and clovers, as they prefer them to brome or fescue. It may be necessary to either spray insecticide, or use a bait to kill them. Baits can be obtained that either use a low dose of carbaryl (Sevin) or a protozoan parasite specific to grasshoppers and crickets called Nosema locustae. The baits do not harm beneficial insects or wildlife like broadcast sprays of insecticides. The Nosema locustae bait is very slow acting, often taking several weeks to take

effect, so it is important to plan ahead when using this product. Burning a stand off in the winter or grazing it down to remove residue prior to seeding can eliminate hiding places for crickets.

Herbicide carryover can be an issue, especially if products containing picloram (Tordon) have been applied within he past two or three years. Avoid using long residual herbicides for at least two years prior to interseeding broadleaf or legume species. Short residual products like 2,4-D are acceptable if done at least a month prior to seeding.

Managing a mixture of grasses and legumes

Once legumes are established in a pasture, it is important to limit or eliminate applications of nitrogen fertilizer and to avoid the use of broadleaf herbicides like 2,4-D. This inability to control weeds with herbicide leads many people to avoid using legumes. Weeds are seldom, if ever, a problem in well managed pastures that are grazed using daily movement grazing as we will discuss.

Rotational grazing, with a frequency of at least weekly and preferably daily, will maximize the longevity and production of grass-legume mixtures. Legumes, especially alfalfa and red clover, respond exceptionally well to rotational grazing. Rotational grazing, especially on a daily basis, also eliminates weed issues. For some reason, when animals are moved daily, they begin to consume essentially every plant, including many species considered completely unpalatable, such as dogwood and sumac. Note the almost complete consumption of many weeds and brushy species in the photo below of a pasture using daily movement grazing with a polywire reel and step-in fence posts. The perceived time commitment to daily movement rotational grazing is usually wildly exaggerated. The time to move a polywire reel and step in fence posts for a herd of 50 cows is only about 15 minutes a day more than simply checking the cows. For this slight additional effort, pasture production often doubles, weed problems disappear, and animals become very tame and easy to handle. Studies that compare total annual labor needs of rotational grazed farms to continuous grazed farms have found that the time commitment to management was actually quite a bit less for rotational grazing, which was a surprise to everyone but those who practice rotational grazing. The “taming” effect of rotational grazing greatly reduces the time necessary for gathering animals and treating sick animals since they become trusting and easy to capture.

Under rotational grazing on a daily basis, weeds and brush tend to be eaten. If they are both nutritious and consumed, why spend money to kill them? Most “weeds” and leaves of brush are higher in mineral content and protein than grass.

Bromegrass regrowth 60 days after haying in control area

Adjacent field to one above planted to a mixture of summer annuals (sunnhemp, pearl millet, BMR corn, sunflowers and cowpeas) after haying. Photos taken in September.

Photo above: Note the much higher production form the plot on the left which includes alfalfa, clovers, chicory, and plantain than the monoculture fescue to the right of the orange line. A more diverse pasture will be much more productive and support much better animal performance than a monoculture.