Many of us take for granted that we can have a refreshing glass of orange juice anytime we want, but there is a dire and growing threat to the US citrus industry.

Huanglongbing (HLB), often called citrus greening, is a bacterial disease caused by Candidatus liberibacter that threatens to wipe out the entire Florida citrus industry and similarly threatens citrus worldwide. This bacteria is spread by a little insect called the Asian citrus psyllid. Once infected, the vascular system of a tree plugs up, the fruit fails to ripen and remains bitter, and the tree loses vigor and eventually dies. Huge areas of citrus have been completely killed by this disease, and the once enormous Florida citrus industry is in danger of being a thing of the past.

An orange tree that is nearly dead from HLB (citrus greening) in bare soil.

The first line of defense attempted against this disease was to bombard orchards with insecticides to kill the psyllid before it spread HLB. Growers soon found that this was expensive and not very effective as it was economically impossible to spray often enough to completely control the psyllid and the trees eventually became infected. Even more expensive measures have been tried, such as placing cloth bags over small trees, and antibiotic injections into the trees (which makes the resulting fruit unsaleable but may save the valuable

trees). Nothing so far has been found successful, and HLB has marched along, leaving devastation all over the Florida peninsula.

But one small citrus grower may have found a solution to citrus greening, and the inspiration for that solution came in the form of a monstrous dead alligator. Edward James owns a small orange grove near Howey in the Hills, FL, that was nearly dead a few years ago. Like other citrus growers, he was waiting for the “experts” to come out with a silver bullet that would save his trees. Edward was following orchard expert recommendations and practiced “sanitation” and “weed control” by keeping the orchard floors free of plant growth and debris. Under this system, the soils were deprived of the tree leaves and twigs and the vital root exudates from understory vegetation that form soil organic matter and feed soil microbes. This barrenness along with heavy chemical applications made the soils lifeless and sterile but not atypical for a Florida citrus grove. A big alligator changed all of that! Edward recounted the story:

After we killed and butchered a huge 12-foot leathery hided invader, we buried the carcass in an orchard that was almost dead from HLB. I had been planting a few cover crops in this orchard to try and help the soil in preparation for the next crop as my trees were almost dead. But in the sterile and sandy soil, the cover crops were only getting 6-8 inches tall except for where we buried the alligator carcass. They grew 3-4 feet tall and were dark green and vigorous! But more importantly, we noticed that the nearby orange trees seemed to be much less affected by the HLB and were starting to look “normal”! That is when it struck me: the solution to HLB is not some new, silver bullet spray or drug for the trees the solution is in the soil itself!

It is now becoming increasingly suspected that soil sterility has predisposed citrus to HLB. It was noticed that trees growing in spots where vegetation control efforts had been unsuccessful were much less affected by HLB. It has also been noted that heavy doses of nitrogen fertilizer seemed to make HLB symptoms worse. Edward observed these phenomena as well and noted that citrus

trees growing in oak hammocks outside his groves were relatively unaffected by HLB.

Based on his observations, Edward decided to reverse the “sanitation” trend and use practices to increase soil organic matter and biology. Of course, burying an alligator every few feet in the orchard would be impractical! Compost could be a good alternative but the price of transporting and applying sufficient amounts proved uneconomical. Then he realized the solution was in what he was already dabbling with: planting cover crops in the orchard, supplemented with whatever organic materials he could acquire on the cheap, such as wood chips. The results have been surprisingly good and seem to be getting better every year.

A fresh mowed cover crop in an orange grove reveals an understory of blooming buckwheat that can attract lady beetles and lacewings, predators of the Asian citrus psyllid.

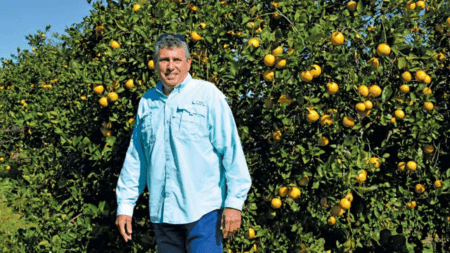

Where his trees were almost dead, Edward now has almost normal trees with excellent citrus yields. Soil organic matter levels have gone from nearly zero up to arange of 3-5%—levels almost unheard of in hot, sandy Florida soils. Most importantly, his input costs are now a third of what is typical in citrus. No insecticides are sprayed. No more herbicides to keep the ground bare, rather his groves have a vigorous understory of cover crops, many of which are nitrogen fixing legumes, which help to greatly reduce his need for fertilizer.

Cover crops can help with HLB in multiple ways. One way is through providing nitrogen in the form of protein. The uptake of nitrogen in the form of nitrate (common with most fertilizers) seems to make the trees more attractive to the psyllid as sap-feeding insects are attracted to plants with high levels of nitrate. Leguminous cover crops can provide much of the nitrogen needed by citrus orchards in the form of protein and amino acids, which are slowly converted by microbes into plant-available nitrogen so there is never a large dose of nitrate present for plant uptake.

Active soil biology may also stimulate the plants natural immune system. The presence of benign organisms can trigger a plant response called Systemic Acquired Resistance (SAR) that makes the plant more resistant to infection. It is also well known that many plant microbes, particularly actinomycetes, produce antibiotics (almost all medically important antibiotics were originally derived from soil microbes) and that plants can take up antibiotics from the soil. Colonization with mycorrhizal fungi has been shown to facilitate transfer of SAR triggering compounds from plant to plant and may also facilitate the uptake of antibiotics from soil. Finally, there are some bacteria that are known to move from soil into the plant vascular system to consume other bacteria, including pathogens.

Cover crops may also be beneficial in managing the psyllid as well. Psyllids are preyed upon by spiders, lady beetles, and lacewings. Cover crops can attract an abundant and diverse supply of benign insects that can feed a growing population of organisms that eat psyllids. Even the pollen and nectar of some cover crop plants, such as buckwheat, can provide an alternate food source to live prey for lady beetles and lacewings, and adults of these species seek out pollen rich environments for egg-laying. There is a parasitoid Tamarixia wasp that is specific to the psyllid, but cannot provide complete control, as it would eliminate its food supply. However, it may be a highly useful tool as part of a more comprehensive control program.

Healthy orange tree with a radish dominated cover crop mix growing below.

Diversifying orchards may also be a useful strategy. For example, a plant called orange jasmine is an alternate host of the psyllid but does not host the HLB bacteria. Therefore, it could be used to surround an orchard or be planted within an orchard to host psyllids that would not be infected with HLB and provide a food source for the Tamarixia wasp and maintain their population. The psyllids also may be repelled by Moringa trees or neem trees, which can also provide alternate income streams.

Avoidance of insecticide use within the orchard is another aspect of managing HLB. Insecticides applied on a frequent basis have not been effective at preventing HLB, but were effective at eliminating predators of HLB and in the long term may have made matters worse. One extra benefit of eliminating insecticide use within the orchards may be that orange blossom honey, an important, historical ancillary product of citrus production, may return. Since insecticide use has become so frequent in citrus orchards, honey bees are no longer placed in them, and thus we no longer get honey produced from citrus blossoms. Replacing insecticides with cover crops just might make it possible to keep oranges, orange juice, grapefruit, lemons, limes, and orange blossom honey on the table!

While most of us do not grow citrus or battle HLB, we can all learn from the principles that Edward is successfully applying to his orange groves. Edward is now promoting his system and cover crops to other citrus growers.

Edward James is an innovative citrus grower and citrus consultant located at Howey-In-The-Hills, FL.

Also check out the 11th edition, our latest Soil Health Resource Guide, over 90 pages packed with scientific articles and fascinating stories from soil health experts, researchers, farmers, innovators, and more! All as our complimentary gift to you, a fellow soil health enthusiast!This article first appeared in the 10th Edition of Green Cover's Soil Health Resource Guide.