From Cover-crops to an Original Ecosystem Management Approach.

Frédéric Thomas has been a French no-tiller for 30 years. Today, he also works as a trainer, teaching others about cover-crops and global Conservation Agriculture (CA). He spends most of his time in France and Europe, and travels annually in the French Indies to adapt CA practices to tropical conditions. Occasionally, Frédéric travels to the US where he worked 40 years ago as a student in MN and MT. Frédéric is the founder of TCS Magazine (the French No-till Farmer) and has been involved in multiple farmer organizations such as BASE (Biodiversity, Agriculture, Soil and Environment). Frédéric’s on-farm experience and agricultural travels keep him evolving and challenging new ideas.

GC: Why did you start out with a no-till approach on your farm?

When I took over the family land, with my different experiences around the world, I knew it was poor land as it was sand with 0.7 to 1.2 % SOM content sitting on water-logged clay. Minimizing cost and time while trying to improve soil was the only possible direction for me. We started by stopping tillage, but the first results were not as good as expected, so we rapidly inserted cover crops into our toolbox. First, it was just oats and mustard. But due to Brazilian influence, we moved to 6–12-way mixes in the early 2000’s with great success.

As my soil fertility was so low, I decided to bring in locally produced compost to bring in basic nutrients as well as plenty of trace elements and carbon. It really helped, even though at the beginning, the Carbon:Nitrogen ratio and my nitrogen availability suffered at first. We have followed this path for more than 20 years and it worked so well that we now have our own composting area on the farm. The product that we get is of a lot better quality (lower C/N ratio) with less woody pieces. With the price of fertilizers in 2022, it also proved to be a great economic strategy.

12 ways “Biomax” cover crop mix drilled in early July after winter barley (picture taken September 15). It is a mix of summer and winter plants sown with red clover to relay next spring. It will be mob grazed all through winter before planting corn in early April.

GC: What results have you seen in your 25 years of experience?

Water management is probably the most interesting one. My soil was extremely dry in the summer and too wet during the winter. I basically was farming in a small bucket! Now, thanks to the roots and the earth worms that open the clay and deepen my soil, the water-holding capacity is six times as great as when I started. This positively influences yields as well as climatic resilience. Now I can also successfully grow winter barley and oil rapeseed or graze cover-crops with sheep during the wet winter period without hurting the soil structure. Another great result is carbon sequestration. I recently entered a program, and I have been credited for offsetting 1.72 metric T of equivalent CO2/ha/year. It is a little extra income, but it is a big recognition of what well-managed agriculture could contribute in terms of climate change mitigation.

GC: Why did you add grazing animals back to your farm?

Another strategy is to first plant a sorghum

cover-crop that brings strategic forage for

the animals during our dry summer and then

relay with a winter legume mix (field bean,

Austrian winter peas and hairy vetch) before

following with corn.

We were observing some pioneers in France and in the US that were starting to use grazing animals stems. It was obvious that there were lots of potential advantages, but we were facing a big obstacle: it was not skills, but time! Animals not only increase work hours, but they tend to glue you to the farm. For multiple different reasons, I happen to live 3.5 hours from my land. To make it work with the distance and the time, the best solution I found was to create a partnership 20 years ago with our first colleague, Christophe. It took me 3 years to find him, but he was happy to work with me and go for CA on his farm. He was running a quite large operation for the area and was also doing contract work, so his time was also limited when it came to animals on the farm. It took us few years before finding our first shepherd, José. He had no land or farming experince, but loved to raise sheep. We set up a business plan for him and he took one year off (in France, it’s possible to take a year to try something like this without the risk of losing your job). Christophe bought 50 ewes, I let him have some land and cover-crop on the farm for free to help him start his business and the composting area employed him half-time to secure the deal. After one year of testing, he decided to stay with us.

GC: Tell us more about the collaborating -it sounds like you have a really unique and beneficial arrangement.

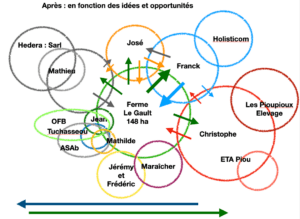

Frédéric uses this graphic to present the way his ecosystem is organized and works. There are a lot more people and items that could have been included, such as two beekeepers,

wildlife and hunting activities, and additional neighbors who are also involved in one

way or another.

We do! We set up a collaboration contract and detailed what we could each bring to the table. His time, agro-chemicals knowledge, equipment and great business acumen and my expertise on implementation of CA in our soil and climate and acces to new networks and ideas. We only priced the machinery, the labor, and some seeds according to local standards and just exchanged our expertise for free. The idea was to try to find a balance without becoming linked financially or in any kind of business structure.

This experience brought us 2 important things. First, we learned to really value the labor: today we exchange at the rate of 30-35€/h which is probably not enough. This way, labor is always included in the economical calculations, and it helps in the management decisions.

Second, this special arrangement enabled us to sum up different skills and networks. There are so many things to address in agriculture, especially nowadays, that it is better to have multiple heads to tackle them.

We organized a similar partnership when our compost supplier asked me if he could get 2-3 acres to set up a composting area on the farm. I let him use the land and some equipment when he needs it, and in return, I have a source of good fertilizer at a great price located in the middle of the farm with no transportation cost. As his business employs permanent labor, it helps us keep an eye on the farm, and he even gives us a hand sometimes. We try to maximize the beneficial interactions.

GC: Have you extended the team or the ecosystem since expanding into livestock?

Like conservation agriculture, this way of thinking and managing business is quite contagious. 6 years ago, one of my close neighbors was going to retire and was looking for someone to take over his small farm. Instead of jumping on this opportunity to extend my farming area, I helped my former farm adviser to take this land and set himself up in farming. He started straight away with sheep and Aberdeen cattle plus cereals, and kept a little advising business. He didn’t have to invest in machinery as he uses mine, and has access to the compost. Letting this land go to a new partner helped me to reduce even more of my workload and increase the profitability on my fields. As with our other colleagues, his success reinforces mine and vice-versa.

GC: Are you still working on the farm?

I am still on the farm in April (spring planting), July (summer harvest and cover-crop drilling) and October (fall harvest, winter crops and cover-crops planting). I like to keep this contact with my land and the real farmer’s life. This really helps me to stay humble because everything doesn’t work as it seems to in books or Facebook videos. Challenges evolve and it is very strategic to stay in contact. I am physically away most of the time, but with the phone and WhatsApp, I follow the fields and the crops, and I bring my point of view when needed. It has always been a big dilemma for me: leaving some work on my farm to travel and get new ideas and new knowledge. With this set up and ecosystem, even if it is not perfect, it makes things much easier, and my colleagues know that in return they will get some “free” information to keep increasing our collective efficiency, resilience, and economics.

GC: What are the next ideas and objectives for your ecosystem?

Some of the members of the ecosystem left to

right : Mathieu (compost), José (the shepherd), Franck (the agronomist converted in Farming) and Frédéric Thomas.

This experience brought us some new ideas. I really think our farms could incorporate a market gardener. We had an opportunity to try this two years ago, and although it didn’t last, we learned a lot with this experimentation. I am also interested in stock cropping. Why not have someone start this as his own operation on our farm?

To make it work, you must think differently, and really concentrate on the diversity of skills and thinking. It can be hard, especially when one of your colleagues is not good at something you are great at. But just think that he will be a master of things you have trouble with. Moreover, each one has his own network that increases the ability to solve problems and address new challenges. Finally, it is a fantastic human and team story that holds together based on trust and strong confidence between each other. Though it can be fragile, and requires everyone to be cautious and give it attention every day, it’s really worth it!

GC: To conclude, what do you see as the future of this ecosystem?

It is very hard to give you an answer, as it evolves like a living creature. Its high flexibility will help it to find solutions as new challenges or opportunities come. This dynamic will also ease the transition with part of the farm, and it is something we are already talking about. Some young colleague could get in, run the operation, and bring youth and engagement. This would allow me even more time to keep traveling in quest of new ideas and innovations to incorporate into our agroecosystem, and also other farms in the country for more economical, agroecological, human and environmental benefits. Time will tell, but I feel secure thanks to this original ecosystem we have built over the time.

This article first appeared in the 10th Edition of Green Cover's Soil Health Resource Guide.

Also check out the 11th edition, our latest Soil Health Resource Guide, over 90 pages packed with scientific articles and fascinating stories from soil health experts, researchers, farmers, innovators, and more! All as our complimentary gift to you, a fellow soil health enthusiast!