Dale Strickler Describes How to Use Wheat Stubble to Provide Pasture

Perennial pastures reach their peak production and quality in the late spring if the grasses are cool-season like fescue, orchardgrass , bluegrass or brome, or in early summer if warm-season grasses like Bermuda or native prairie. Animal demand, however, if in a spring birthing operation, will peak in late summer and fall, prior to the typical fall weaning. Additionally, perennial pastures are quite vulnerable to overgrazing in late summer and fall, when the grasses are building root reserves and new tillers for next years growth. A means of providing abundant, high quality nutrition from otherwise idle cropland during late summer and fall could add greatly to livestock performance and improve future pasture productivity

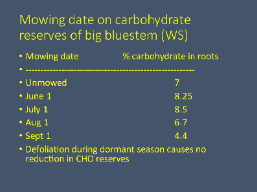

Note how late summer grazing is the most detrimental

to plant carbohydrate reserves; this is when pastures most need rest

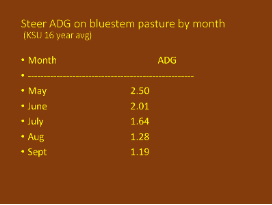

Note how animal performance in late summer is less

than in early summer on the same grass

However, while late summer and fall are the opportunities to improve production from both pastures and animals, it is winter when most costs of feeding livestock are incurred, because most winter-time nutrition is derived from expensive hay or silage. Since grazing is far cheaper than hay or silage, given equivalent nutrition, wouldn’t it make a lot of economic sense to develop a system of grazing for the winter?

And what if we could accomplish all the above by devising a system that could increase animal gains, improve pastures, and reduce costs while simultaneously improving the soil in neighboring cropland acres and improving subsequent crop yields on those acres? Keep reading to learn about just such a system.

I can’t devise a single cover crop blend that can provide nutritious forage during that entire period. But I can devise three different cover crop combinations that can be used in sequence to completely cover the needs of most grazing livestock over much of the Great Plains, and with some minor modifications, over most of the eastern US as well, as long as there is sufficient acreage of open wheat stubble that will be rotated to spring planted row crop the following spring.

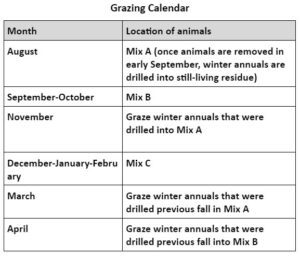

The plan involves three separate forage mixtures, planted adjacent to each other to allow easy seasonal livestock movement. Three acres (one acre of each forage mix) per 1500 lbs animal liveweight is a reasonable acreage to allot for this time period given sufficient rainfall and soil productivity; in more arid areas, the acreage per cow will likely need to be increased.

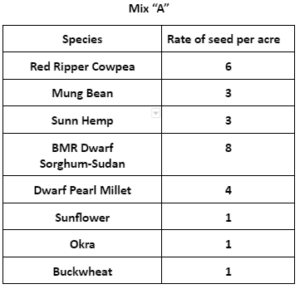

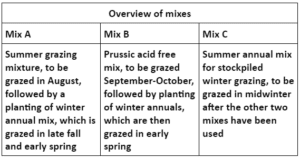

The first combination involves the planting of two separate mixtures in sequence on the same piece of land. The first of the two mixtures is a blend of summer annuals based on a dwarf BMR sorghum-sudangrass and dwarf pearl millet, and this mixture is planted immediately after small grain harvest and is grazed as soon as it hits the target height of 24 inches, which is usually 30 days or so after planting in the heat of summer. After this mix has been grazed off, a winter annual mix can be drilled into the live stubble, and the regrowth of the summer mix allowed to combine with the new growth of the winter mix to produce a very nice fall grazing blend of high protein winter annuals with the high energy, high dry matter frozen growth of the summer annual grasses. A sample summer annual mixture along these lines might look like this: (note that, depending on soil nitrogen status, soil type, drainage, etc and fertilization philosophy, this mix could vary greatly)

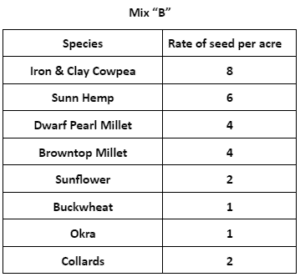

The second combination is similar to the first one, but with no sorghum-sudan, since sorghums can carry a risk of prussic acid toxicity during the time of frost. This combination is designed to be grazed later in the fall than the previous mix, and after it is grazed, it can also have a winter annual mixture drilled into it to provide spring grazing.

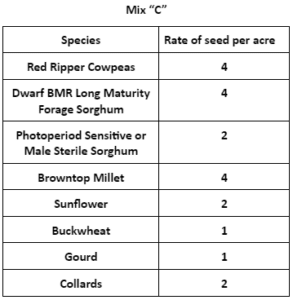

The third mixture is based on non-grain-producing BMR forage sorghums, which retain forage quality well after frost, along with a sprinkling of other species that retain quality well into winter.

This article first appeared in our “Keepin’ You Covered” email newsletter where we share 1 soil health topic, 2 success stories and 3 learning opportunities.

If you’re excited to learn more, sign up for our bi-monthly newsletter here.